Saint Helena

Early history and significanceRugged and Remote

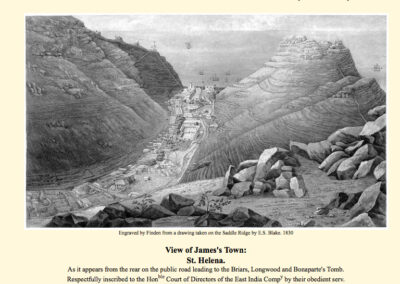

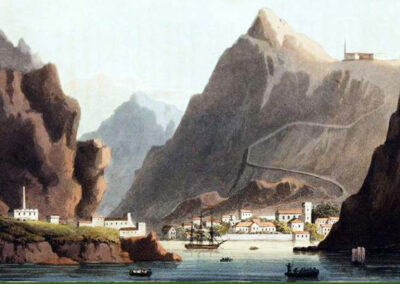

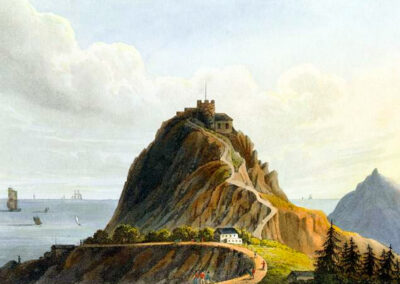

Deep in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean, lies a tiny island, a mere 16kms from north to south and 9kms at its widest from east to west. The island was first discovered in 1502 by the Portuguese explorer in service for the Spanish, Jaoa da Nova, who named it St Helena. Approached from the sea, it looks like little more than a rock — volcanic, jagged, forebiddiing. Here and there, patches of green can be seen where the rock so allows and between rock spires at its north and south ends is a valley of green. The green is not the lush semi-tropical forest one finds on other islands at 15 degrees or so south latitude; the green of St Helena is a ground cover of shrubs. Goats, left on the island by sailors perhaps centuries past, devoured the rest. Its rugged topography limits its arable land and space for settlement.

Re-provisioning Stop

Saint Helena was conveniently located in the southeast trade winds, the wind system which ships returning from India and the Far East around the Cape of Good Hope (Horn of Africa) used to blow them north back to Britain. It was just about at the latitude of Saint Helena that provisions aboard got low so the little island received many visitors from British Navy and merchant vessels. The island offered wild goat, fresh water and fruit (Not until 1753 would a Scottish surgeon in the Royal Navy, James Lind, discover that lemons cured scurvy. When, 40 years later, the British Navy finally made lemons a dietary requirement on all navy ships, many thousands of mariner’s lives were saved each year). Then in 1657, Britain claimed the island as a British possession. She had settled it, fortified it, stationed troops there and subsidized it, none of which the Dutch or the Spanish before them had done. Britain had met the internationally recognized criteria for territorial possession.

Return of the Dutch

Prior to 1657, the Dutch had abandoned the island in favour of developing a colony and harbour at the Cape of Good Hope. It seems the Dutch realized too late that St Helena was a far superior re-provisioning stop than the Cape, for in January of 1673, five Dutch warships appeared at St Helena and took possession, obliging the Governor, soldiers and other British officials to leave. It was a civil, orderly and bloodless affair which might have gone something like this:

Historical Fiction

In the early hours of the 14th of January, 1673, five Dutch man-o-wars appeared off the tiny Island of St Helena. Two of the ships patrolled the island’s perimeter; three including the flagship, anchored off Jamestown, the island’s only settlement. From the flagship, a longboat was launched with a uniformed officer of rank seated in the stern. Amidships was a pole bearing at the top the Dutch flag and below it a white flag declaring the officer’s intention to talk terms.

By the time the landing party was nearing the dock, Governor Simpson was standing at the foot of the jetty, casually erect, arms comfortably clasped behind his back. Behind him on his right stood a soldier at attention. At arm’s length he held a standard upon which the union jack fluttered uncaring in the warm trade winds. On Simpson’s left stood Lieutenant Davis, Commander of the 51st East India Company Regiment, St Helena. Behind them stood a platoon of soldiers, rifles shouldered.

The Dutch officer and four crew tied off the longboat, climbed the ladder to the landing and strode in unison to where the governor was standing with what Governor Simpson later described in his report as “smug purpose”.

The officer in charge began. “I am Commander Hans De Clerke of the Royal Dutch Navy. I am here on the orders of His Highness, King Leopold the Fourth of Holland who demands your immediate surrender of the Island of Saint Helena, a rightful possession of Holland, and the withdrawal forthwith of yourself and all military and East India Company personnel.”

De Clerke paused then, in part to allow Simpson the opportunity to respond as any gentleman would, and partly to collect himself for the last half of his fastidiously rehearsed speech. This was, after all, a historic moment. Any error on his part would spell the end of his burgeoning career.

Simpson took the hint and spoke. “I am Governor Thomas Simpson, chief representative of the Honourable East India Company on the Island of St Helena and by the terms of the company charter, agent in turn for the British government. First, on behalf of the British government and the people of St Helena, I wish to thank you commander, for your decent approach to this matter. If we can resolve this without bloodshed, why not?

You have had a long voyage. No doubt you are parched. Might I suggest that you and I alone continue this conversation, as a dialogue between gentlemen, in the pub across the way.” Simpson turned and pointed to the Pelican Pub, the island’s only watering hole, not 200 feet from where they stood.

The Governor’s informality and affable nature caught De Clerke off guard. This man was not the boorish haughty Englishman he’d come to loathe. More likely he was an ineffectual puppy who, through flattery and platitudes, was promoted beyond his capabilities. When the company discovered their error, the commander mused, it ‘promoted’ Simpson to the loneliest outpost in the British Empire where he could do no harm, to the rest of the empire, at least.

For a brief moment, De Clerke said nothing. Should he ignore Simpson and finish his speech or accept his invitation and learn more about this curious man. After what seemed like minutes to those present, yet in truth were seconds, De Clerke replied, his words were slow and measured, and edged with the tone of a man intent on being in charge, “I accept sir, but be forewarned. This is not a negotiation. My orders are explicit and unalterable.”

“Of course. I understand commander. Lieutenant, see that the pub is vacated immediately save for the cook and serving maid. Place four guards on the establishment, two front, two back, matched, with the commander’s permission, with four of his own men. Then kindly stand down.” With a smile and raising his arm in a gesture of welcome, Simpson offered up a beguiling “Shall we?”

Simpson knew that St Helena was lost. Their troops were hopelessly outgunned, the fortifications a mockery. Yet perhaps there was room to bargain for the well-being of the St Helenians left behind and reach agreement on an orderly departure for those who must go. Britain will settle this score soon enough, he thought. His job was to save lives.

The two men sat by a window in the pub, De Clerke ill at ease, Simpson relaxed. The Governor’s lively face and expressive hands could well have led the ill-informed to believe that the man sitting across from him was an old and valued friend. “Breakfast commander?”

“Thank you yes. I’ve had my fill of beetle-infested hard-tack.”

“I’m sure you have. Gretchen, kindly drum up a hearty bacon and egg breakfast for Commander De Clerke and me, with tea forthwith if you please.”

“Right’ away Your Grace.”

Simpson shrewdly kept the conversation light. He told the commander his grandmother was Dutch and that as a boy during peacetime, he had visited her often in Holland and loved it. He tried out his smattering of Dutch on the commander who grimaced, laughed and corrected him. They found commonalities among their favourite authors and artists and they discovered that both of them loved to tramp the high country when the rare occasion presented itself.

Breakfast was a delight beyond the commander’s imaginings — yes, salted pork came his way on occasion, but never eggs and never fresh bread. And tea rarely reached his level in the social order. An hour and a half had passed by the time De Clerke wiped up the last of breakfast with a morsel of bread. As he did so, he spoke. “Governor Simpson, my orders are to plant the Dutch flag and take formal possession of St Helena. How I do so is entirely up to me. With your active cooperation, we can make this process quick and painless and, I should say, bloodless. Are you willing to cooperate to that end?”

It was Simpson’s turn to pause, his face, for the first time, creased with concern. “You and I, commander, are the servants of our nations. We find ourselves enemies in this time and place, yet in the midst of rubbing shoulders over breakfast, we discover we are much the same — fellow human beings with similar interests and desires. As I see it, my foremost duty is to serve and protect my people. You no doubt believe your duty to be the same. As for the territory of St Helena, that is for others to sort out.

Yes commander. If you can offer those of us who must leave safe passage, and if you can provide assurance that those who stay will be fairly treated, and if you require no acknowledgements from me, verbal or written, which state or imply that Britain is forfeiting possession of St Helena, then you have my full and active cooperation.”

It was, by then, clear to De Clerke that he had grossly misjudged this man. Far from the inept, blustering fool he had taken Simpson for, his host was more than a match for himself in charm, grace and perhaps intelligence. De Clerke replied, “All of that is acceptable to me, Governor. Understand, however, that you have 3 days to provision for the journey, withdraw all British ships, military and administrative personnel, and depart. Bombardment of Jamestown will commence at one hour past dawn on the fourth day should any ‘enemy aliens’ remain.

Simpson knew that there was no choice. Resist and witness the slaughter of dozens of men, women and children, or leave. The entire St Helena defence force amounted to the legal requirement to meet the criteria for territorial possession, and no more — 43 East India Company soldiers, 12 outdated cannon and ludicrous fortifications properly described as quaint.

Simpson spoke, “As you will, commander.”

Then De Clerke, “We have a gentlemen’s agreement then, Governor. Let us set to the task. I thank you for this breakfast sir. It was exquisite.”

As agreed, the evacuation was quick and the turn-over went without incident. Governor Simpson and his entourage embarked on the HMS Defender and left for Brazil, the nearest friendly port. Military personnel departed on the HMS Rage with orders to head north on the lengthier voyage to London with all speed and report the incident.

The British Response

Historical Fiction

Eventually (it took time to voyage vast distances), word of the St Helena snatch got back to Westminster and the Admiralty. In the halls and backrooms, clutches of animated men gathered; exchanges were heated and edged with anxiety:

8:30am August 14, 1673. A meeting was convening in the Admiralty board room, London. Present was Admiralty Chief of Staff, Admiral Sir Henry Clarendon. To his right, Chair of the Honourable East India Company, Sir Charles Jessop and continuing right, Jessop’s department heads: for trade, Richard Atwell, for the military, General George Friars, for Marine Transport, Mr Edward Gibbons, for Public Works, Mr Sethford Jones and the omnipresent Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, Mr Samuel Pepys.

Sir Henry addressed the group. “Good morning gentlemen. I must tell you that this news of the loss of the Island of St Helena leaves me apoplectic. Suffice it to say I am stunned that this has been allowed to happen. How is it possible that this little island, which we took for ourselves when the Spanish and the Dutch saw little use for it, is back in Dutch hands. Back in Dutch hands, gentlemen because, no doubt, they realized their error — the error being that their colony on the Cape offers no fair harbour and thus, no opportunity for serving as a re-provisioning stop for their Far East trade.

In other words, until this incident, they were hooped gentlemen, or at the very least, severely disadvantaged. Without St Helena, they have been obliged to re-provision on the West African coast, adding foul winds and a full two weeks to their voyages. St Helena is the key to our getting the upper hand on the Far East trade and squeezing the Dutch out. The stakes are incalculable.

On top of that gentlemen, I needn’t remind you of the critical importance of St Helena as a base for naval operations from which and by which we can achieve supremacy over the South Atlantic and thus, more fully, command the Far East trade. It is my concerted view, gentlemen, that we must toss the Dutch out of Saint Helena and do it quickly before they fortify the island.”

The British promptly re-took St Helena, greatly improved the fortifications, added more soldiers and strategically positioned over 250 cannon. The Dutch never returned.

The Caldwells of Saint Helena

Almost one hundred years later, on 17 October, 1770, a soldier arrived at Jamestown. His name was Lieutenant William Caldwell, aged 30. With him was his pregnant wife, Elizabeth. William had been ordered to Saint Helena to co-command the island’s regiment. Over the next 4 years, the couple had two children, Ann and William. Then, in 1774, William died and was buried with military honours. Elizabeth, left with two young children, likely wasted no time securing another partner, as it was an impossible task to care for children and put food on the table, particularly for a woman.

Elizabeth’s second partner’s name is not known. They had two boys, Richard and Daniel, who were given the Caldwell name, perhaps to match that of their mother, who kept William’s surname. It’s likely that this was a common-law relationship as no marriage record can be found. These two lads, although they carried the Caldwell name, were not, then, Caldwells by blood. The youngest of the two, Daniel, is the earliest known non-Caldwell Caldwell to whom I am directly related. He is my third great grandfather. And this is where the story of our intriguing Caldwell family begins.

In the late 1700s, Daniel Caldwell, a free white and Mary Manay, a slave, were born. They grew up, Mary was freed and she and Daniel married and had children. Their youngest child was Daniel Richard Caldwell, born in 1816. Daniel Richard Caldwell would eventually become a key figure in the early governance of Hong Kong. Perhaps too, he is a key figure in the history of your family, for Daniel and his Chinese wife Mary Ayow Caldwell, raised 12 biological children and adopted over 20 Chinese children in need.

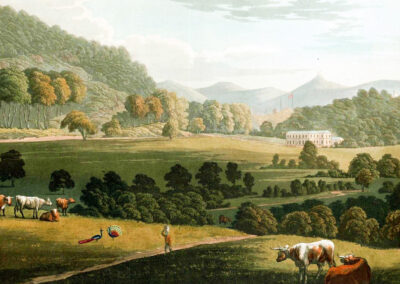

In 1815, a year before Daniel Richard Caldwell was born, the self-styled emperor, Napoleon, captured by the British, was placed in exile on Saint Helena. His presence on the island proved a boon for the island economy. A much reinforced military and myriad services were required to keep Napoleon and his entourage happy. Then, in 1821, Napoleon died and a large portion of the island economy died with him. Listen in while Daniel and Mary ponder what they will do next…

Historical Fiction

The British East India Company, which manages the island, has made the men of the 51st Regiment guarding Napoleon a severance offer. Daniel Caldwell, who is in the regiment, runs home for lunch to tell Mary, his wife, the news. The children are in school.

Heaving from the run home, Daniel crashes through the door of their little cottage. Mary, angered by the violent entry, yells “What is the meaning of this, then? Have ya lost all sense of decency, Daniel Caldwell?”

Daniel blurts out the news. “Mary, Napoleon is dead.”

Mary’s anger turns to fear. “Oh, my goodness. What does that mean for us?”

Daniel continues. “A man from the company came and spoke to us this morning. He said the company is offering free passage and a 3 month living allowance to those willing to go to Penang. The ship sails in 2 months.”

Mary slowly sits on a kitchen chair. “Oh my, Daniel. How can we possibly leave? You and me were born here. We’ve never been anywhere else. We know nothing about the world. My family came to Saint Helena in 1689! As slaves. Their poor beaten bones lay up on that ridge. Daniel, everybody we know, everything we know, is on this island. And here we are, with 4 young children, us, a mixed race couple, me a freed slave, thinking of going to a place we know nothing about, with no way to return to the island.”

“Mary, I am as terrified as you. Yet must we not think of our children? This is an opportunity to give them a future, a real future, out in the world. I believe we owe them that.”

For a brief moment, there is silence, then Mary responds, “You speak wisely, my dear husband. I must put aside my fears, think of the children.”

Daniel walks over to where Mary is sitting and gives her a hug. We have time. Let’s sleep on this.

Two months later: [Bell rings] Cast off, Mr McGuire. Unfurl the squares. All was quiet from the passengers lining the starboard rail as Southern Venture caught the wind and eased from the dock. It was done. The Caldwells were heading for Penang.

Post Script.

Daniel died in Penang in 1828. The family moved to Singapore where it remained. One son, Daniel Richard Caldwell went to Hong Kong where he spent much of his life working for the colonial government. Because he could speak 5 languages perfectly, his presence was essential to the every day running of Hong Kong. Daniel married a Chinese girl, Ayow Chan – Mary Ayow Caldwell. Daniel and his Mary became devout Christians. They had 12 children and adopted over 20 more. Many of you reading this may be descendants of those adopted children.